The book contains a series of articles written by Clifford (above) in the summer of 1955 and published in the Macclesfield Express under his non-de-plume ‘The Stroller’.

In the preface, Clifford explains: “There is something which appeals to me about a valley. Perhaps it is because we can be alone with nature; we can get away from the noise and bustle of workaday life.”

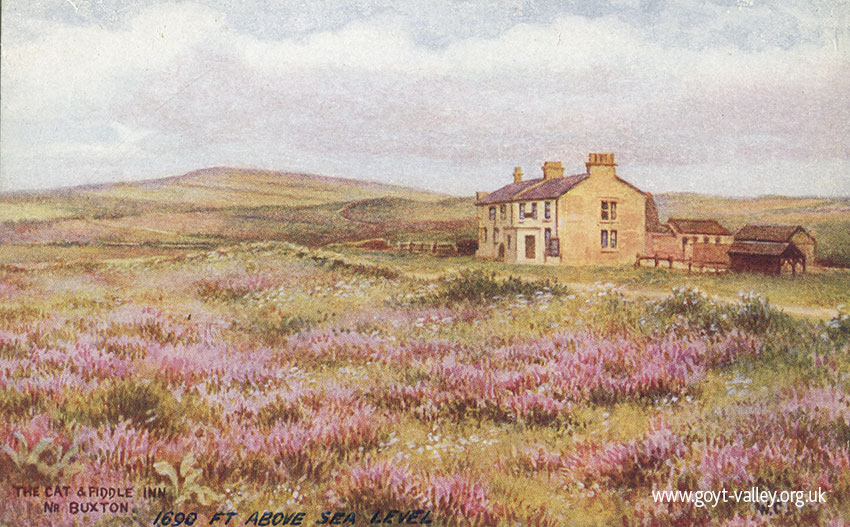

Chapter 1: The start of the journey from Cat and Fiddle to Goyt Bridge

MANY are the occasions I have walked through the valley of the River Goyt for the sole pleasure of taking in the beauty of the surroundings.

I have been at all times of the year. In winter when the snow has lain so deep that I have sunk into it well above my ankles at almost every step: in autumn when the bronzed moors, rising precipitously from the stony bed of the river, have shivered in the gentle breeze giving it a loveliness surpassing description, and then I have returned in summer to see the great transformation worked by nature. The greens of the bladelike ferns and the bilberry bushes are matched by the purple flowers of the heather.

It is the popular view that it is in summer that the valley looks its best. Personally, I can never quite make up my mind. To me there is something thrilling about the wild appearance it has in winter. But those are my own views.

This journey is being taken not merely for pleasure, although I have no doubt I shall have plenty. I am in search of knowledge; knowledge of the people who through the centuries have loved and worked in close proximity to the river. I am tracing the river from its source on the moors just below the Cat and Fiddle to where it joins the Mersey near to Stockport, and I hope to learn much.

Beyond Taxal it will be to me, a journey of adventure. When we in this part of the country talk about Goyt Valley we refer to that part from the main Macclesfield-Buxton road over the old Errwood Estate to Taxal.

As you penetrate further into the valley new vistas open up. Parts of the valley have been dammed to provide reservoirs to meet the needs of Stockport. There are sections where the water is still used to keep the wheels of industry turning. There will be stories of tragedy and romance.

On the first stage of my journey I was fortunate in being accompanied by a charming lady of 76 years who lived for a great number of years on the Errwood Estate and received her early education at the small private school, now disappeared, which stood quite close to Goyt Bridge.

With her as my guide I was able to picture what that delightful area round about Errwood looked like when the Grimshawes were in residence at the Hall.

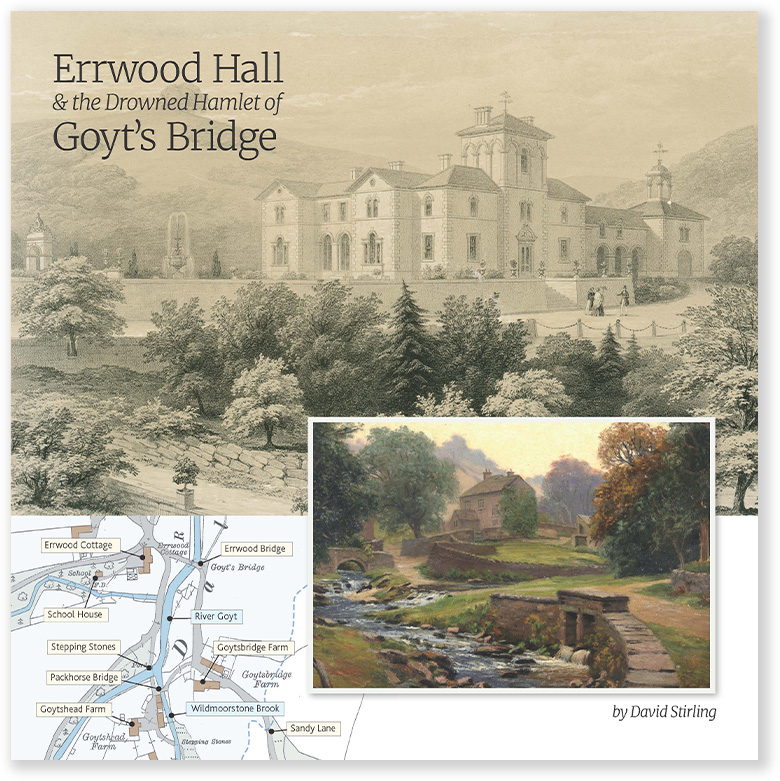

The farms, the cottages, and most of the hall and private chapel have now been demolished, and all that remains to remind us of the days when Errwood was a happy and flourishing little community, practically self-contained, possessing even its own coalmine. are the ruins of the hall, and the rhododendrons, but more about that later.

Sheep are normally very timid animals, but in these parts they have become so accustomed to being fed by visitors that they will rush up to any car which stops by the roadside and beg for morsels like hungry dogs. I have even seen them enter the North Western bus after it has stopped at the Inn. They have become quite an attraction among the young people brought to this open moorland country by their parents.

The Cat and Fiddle Inn has the distinction of being the second highest Inn in England and stands 1,690 feet above sea level. It was built early in the 19th century by John Ryle, of Macclesfield, who was a banker in the house of Daintry and Ryle, in the days when there were so many private banking houses. Daintry and Ryle had premises on Park Green, Macclesfield. John Ryle acquired considerable wealth and in turn purchased the Henbury and Errwood estates.

The exact date of the building of the Cat and Fiddle is not known, but in 1831 it was described as “a newly erected and well accustomed inn or public house called and known as the cat and fiddle.” Many attempts have been made to explain the name of the inn.

Local tradition used to state that the inn received its queer name from the fact that an early Duke of Devonshire used frequently to drive along the road and would stop at the summit to enjoy the view and pass half an hour playing upon his fiddle, to which instrument he was greatly devoted. Presumably he went to play on the moors because there he could annoy no-one but himself.

There are scores of other theories. By some it is said that it was named in honour of Catherine le Fidele, wife of Czar Peter the Great, while still another is that it merely indicates the game Cat (trap ball) and a fiddle for dancing, which is probably the true one. Over the main door of the inn is a carving of a cat playing a fiddle.

The inn has figured prominently in many sporting events and perhaps the most famous was the record set up some years ago by Macclesfield auctioneer, Mr. A. Stanley Turner, who succeeded in driving a golf ball from Macclesfield to the Cat and Fiddle in 64 strokes. An account of the feat printed in the Macclesfield Courier at the time reads:

“Never has such a record been set up by any golfer as that achieved by Mr. A. Stanley Turner and his friend Mr. J. S. White, both members of the Macclesfield Golf Club, when they drove a golf ball to the Cat and Fiddle Inn from the junction of the old and new roads to the Walker Barn up Buxton Road. The distance as the crow flies is about five miles, but the difficult nature of the course must have lengthened it by fully half a mule.

“There is a rise of more than a thousand feet between Macclesfield and the Cat and Fiddle. The country is broken by deep gullies and water courses, there are numerous quarries and the last mile is over rough moorland. The players were allowed to tee up for each stroke within two clubs length of the lie. but this was the only change from the ordinary golf rules.

“The routes taken differed slightly. Mr. White derived some advantage from playing over two awkward quarries at Windyway Head, but Mr. Turner probably made a better course thereafter. Mr. White arrived first at three minutes after noon, and he played up the wooden porch of the inn with his 83rd stroke.

“Some difficulty at a quarry half-a-mile short of the inn had cost him several strokes. Ten minutes later Mr. Turner arrived. He had covered the distance in 64 strokes. Thanks to the efficiency of four caddies neither player lost a ball.

“Mr. White is handicapped at 11 and Mr. Lurner is at scratch. Mr. Turner’s arrival at the Cat was a notable one and he finished with a fine mashie shot. The ball caught the gable end of the inn and bounced back 30 yards.”

But let us get on our journey.

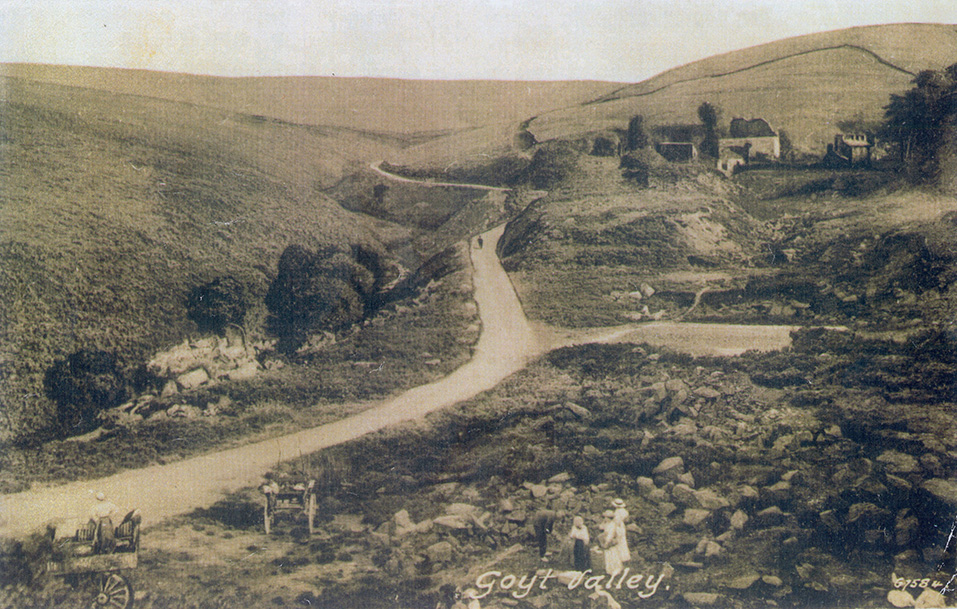

At the beginning, the Goyt is just a thin silver streak forcing its way through the bracken and heather. “The turf’s like spring and the airs like wine”. wrote Masefield. He must have been at a spot like this when those words came to him.

The road along which I was walking down into the valley was the main road into Derbyshire before the top road into Buxton was cut. On the left are the foundations of the house which in years gone by was the stopping place for the coach before arriving in Burbage. The stepping-off stones which assisted the passengers to alight were removed only in recent years.

The moors hereabouts are riddled with old coalshafts, for at one time a considerable amount of coal was obtained from these parts.

The river gradually thickens out as it rolls over crags and rocks and is joined by the numerous riverlets from the higher ground. They find their way to the valley through crevices with the most charming names, such as Ravens Low, Foxhole Hollow, Deep Clough, Stake Clough, whilst one of the streams is known as Wildmoorstone Brook.

As the speed of the river increases, large boulders try to stem its progress, but all they have done is to create pools and waterfalls.

The further I walked, the higher rose the ground on either side of the valley and on my right the purple-tipped heather covered a higher portion of the hillside. The road twists and turns as the scenery quickly changes.

According to Mr. Edward Bradbury, whose writings on the Derbyshire countryside were very popular towards the end of the last century, this quarry was first worked by members of the Pickford family, better known as the originators of the parcel vans. Close by there is a wide opening in the valley where formerly stood Goytsclough Mill.

I went to investigate this charming little spot. Water from the tiny stream which flows through Stake Clough over the moorlands was cascading over the rocks before racing along to fall into the Goyt.

Years ago when the Mill was standing, this water was used to drive the water wheel. There is now no sign of the mill, or of the three sturdily built cottages in which employees lived. The mill was last used for the making of paint.

It was at this point that my 76-year-old companion (to whom | promised not to divulge her name) commenced her story of the Valley of the Goyt, and a delightful story it is. I had arranged for her to be taken to the valley by car, although judging from the way in which she walked and climbed I have a feeling that she could have come on foot all the way from the Cat and Fiddle.

She could not remember the mill being worked, but she recalled the many occasions she had climbed the stone steps – which are still there – to watch the waterwheel.

There were quite a number of farms and cottages in the valley in those days, and the people living in them thought nothing of walking from Macclesfield to Errwood and Goyt Bridge after they had done their shopping.

My companion had many stories to relate. The glimmer of the candles providing the illumination in the cottages by the old mill would no doubt be welcome signs to the travellers in those days.

We made our way to Goyt Bridge and then up the three quarters of a mile drive to what remains of Errwood Hall, and all the time my companion was living over again the happy days of her youth among the small community whose homes were on the Errwood estate before a large portion of the valley was drowned to make the Fernilee Reservoir for the Stockport Corporation.

To prevent the danger of pollution, farms were closed and buildings demolished. Today this is a valley of happy memories, and as I walked through it I could imagine that the ghosts of those who had lived here in years gone by were walking about feeling not a little angry that the buildings on which they had spent so much care erecting had been pulled down.

Periodically my companion would pause and recall some little incident and I felt that she could see again the Mistress of Errwood driving in her coach and pair from the hall and through the valley, now under water, to Whaley.

The last to reside at the cottage, or as it was known “The lodge” was the head gardener, Mr. Oyarzabal, a Spaniard, and his Irish wife, who was a teacher at the private school of the Grimshawes which was sited on the land just inside the main entrance to the grounds of the hall.

I was told of the great beauty of the gardens round “the lodge”, and of the private coal mine in the hall grounds. The man getting the coal would crawl along the opening pushing a barrow in front of him. After the best of the coal had been taken to the hall the “slack” was sold to the cottagers and farmers for a few pennies a hundredweight.

On the opposite side of the river were two farms, Goytshead and Goytsbridge. The Hibberts lived at one and the Ferns at the other.

Page update Jan 2021

Clifford’s ‘Goyt Valley Story’ is now available to read in full as a downloadable pdf. Click for details.

Interesting to read this. I got intrigued when I saw a memorial plaque to Mr Rathbone while walking near Gradbach in the Peak. For some reason I always assumed it was a novel along with Dane Valley Story but this makes more sense. Will have to try and get hold of a copy.