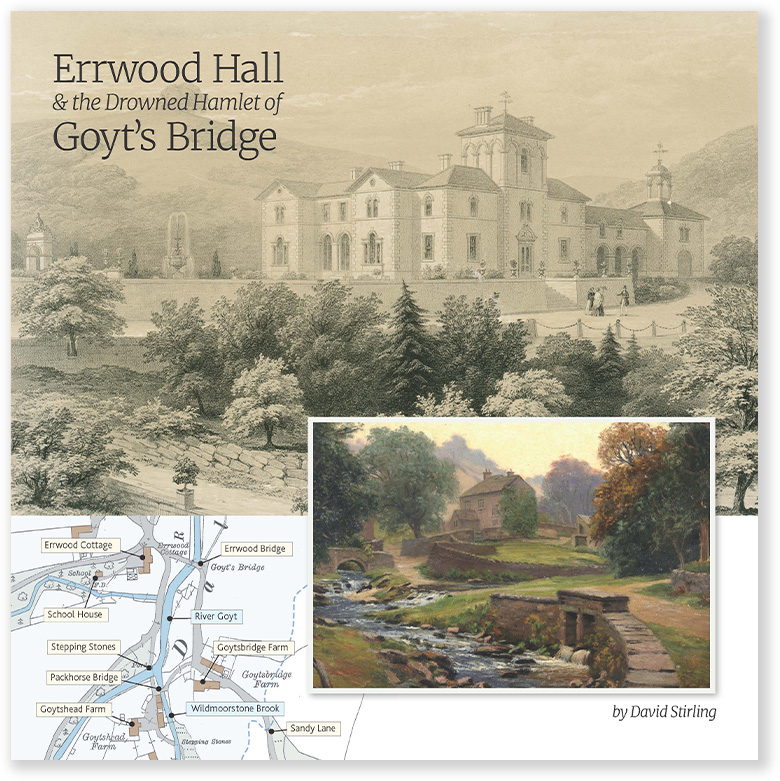

Above: The hamlet of Goyt’s Bridge which now lies under the waters of Errwood Reservoir. I’ve circled Errwood Hall in the distance. The large barn mentioned by Crichton may be the one at far right.

I’m not sure when the photo was taken – possibly in the 1920s. Click here for more information about Goyt’s Bridge.

Above: Crichton’s book has been out of print for many years. But I managed to track down this battered second-hand copy.

This is the second of three posts reproducing a chapter from Crichton Porteous’s ‘Peakland’, published in 1954. The chapter is titled ‘Goyt Recollections’. Click here to read the first part. (The text is Crichton’s but the photos and captions are mine.)

Many persons can recall when Goyt’s Bridge was a hamlet, often bright with flowers. Now where the cottages stood are heaps of rubble, and the big barn that remained for some time after the cottages is gone also.

I well remember the astonishing sight of a stack of several hundred fleeces in that barn, after most of the farmhouses in the water-gathering area had been abandoned and some three to four thousand acres were being shepherded by one man.

I had never seen so many fleeces together, and have not done since. They had a creamy sheen that made me think of cream-coloured narcissi; a queer comparison, perhaps, but the rolled fleeces conveyed the same suggestion of cleanliness and aliveness as fresh flowers.

Behind where the hamlet was is Errwood Valley and relics of Errwood Hall. The last occupiers were two old ladies who used to drive regularly in a carriage and pair down the Goyt Valley by sandy road (most of it now under Fernilee Reservoir) to the Long Hill road and so to Whaley Bridge or Buxton.

Between the wars the house was still well kept up. Then the sisters died – they were the last of their line – and for a short time the Hall was a hostel for ramblers.

At my next visit it was being dismantled because of the reservoir scheme. Contractors had paid a lump sum for what they wanted. The best stone had been taken, the rest left, and none who see what is there now can form any proper idea of the beautiful old home.

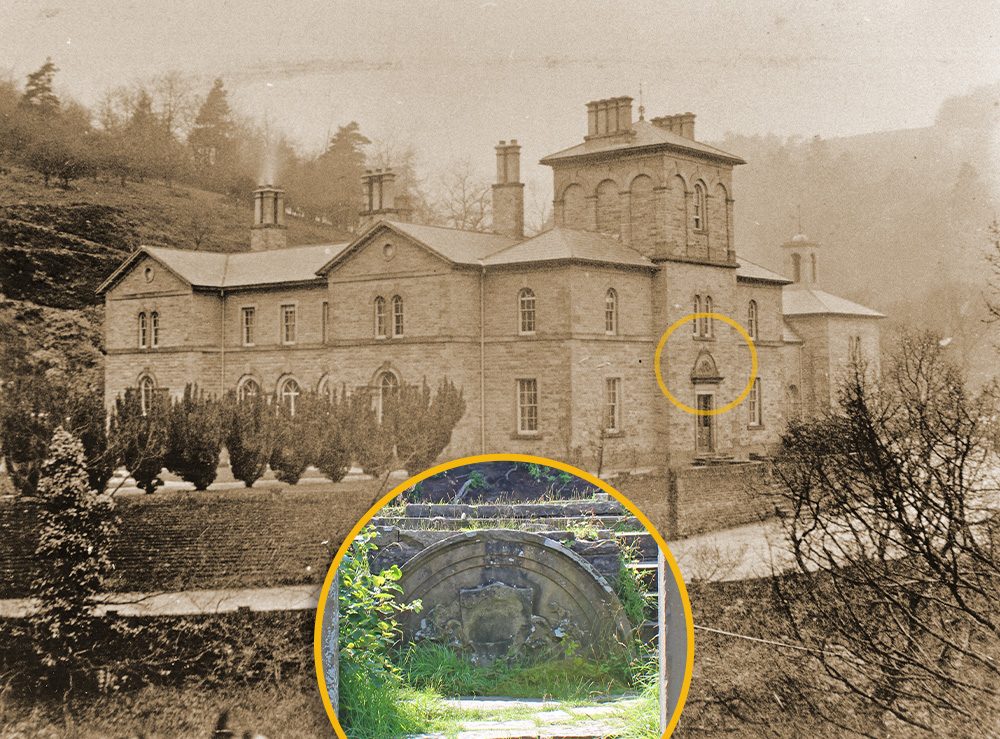

Above: The ornamented arch lay at the southern end of the gardens – to the far left in the photo of the hall. The arch has long since gone but the steps remain. (Click to enlarge.)

Above: I’ve circled the Grimshawe crest which once sat above the main door on this photo of the hall, probably taken in the 1920s. The remains of the stone carving now lie just within the entrance door at the ruins. The chapel was on the first story to the right, next to the bell tower.

It was a double-winged house with a central tower, all standing on a broad terrace looking south. At the east end in the upper storey of a long extension was the private chapel. At the west end of the house a french window gave into a terraced garden.

Wide steps led to the front entrance. Over it was a proud stone dragon, and above the tower a proud metal dragon told the way of the wind. The dragon was the crest of the original Grimshawes.

The last Grimshawe, a daughter, was married to Gosling, and the name became Gosling-Grimshawe. In the gardens was an ornamented stone arch surmounted by a bird and a large “G”.

Errwood Valley is still noted for the show in spring of rhododendrons and azalea blooms, but the best place to see them from was the upper room of the tower. One almost seemed to float on colour, and the scent coming up with the damp and peacefulness of evening made one think that no place could be more beautiful.

After such memories, to see the raped building at first was pathetic, though now nature has softened the despoliation somewhat.

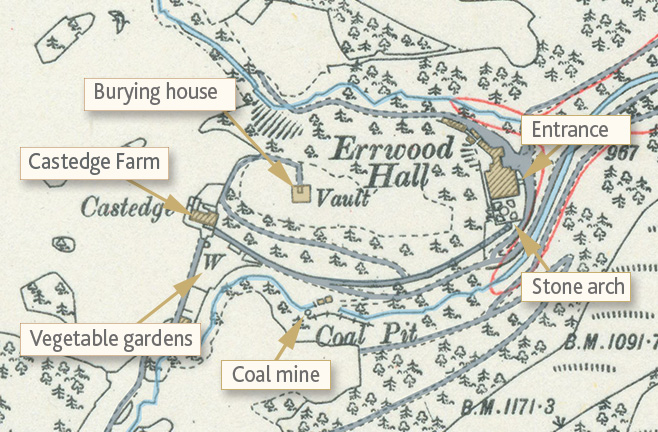

Above: The burying house mentioned by Crichton is shown on old maps as a vault. (Click for more on this now demolished building.)

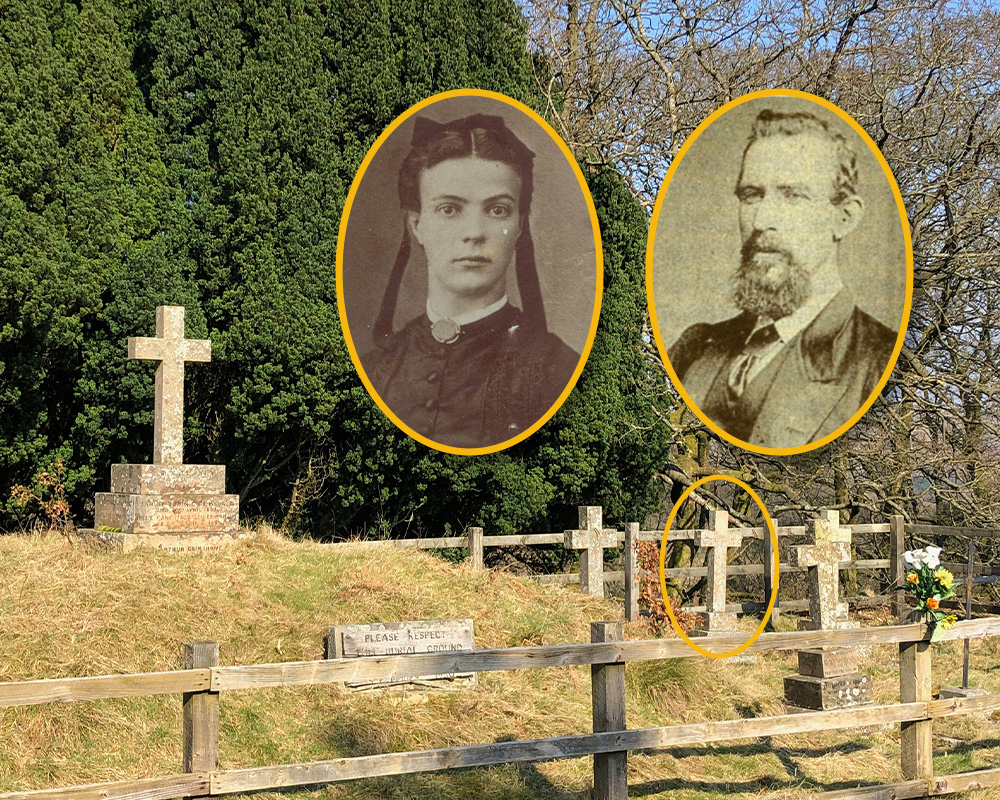

Above: The grave of John Butler, the captain of the Grimshawe’s ocean-going yacht, and his young wife Hannah is second from the right on the back row at the hill-top cemetery. (Click for more on the graves.)

On a quiet knoll behind the Hall the private burying ground had received dependants as well as members of the family. One stone commemorated a seaman, aged fifty-five, who for thirty years had been captain of a Grimshawe’s yacht; another stone, a Frenchwoman, presumably a governess – a strange place, this wild glen, for her to die in, so far from her native land.

The last stone was dated 1911, to a gamekeeper, Pownall, who is remembered to have been very well off, having left £1,000. Any tenant or worker on the estate had the privilege of being interred there.

Privilege it must have seemed when the estate was flourishing, though somewhat diferent now – a forgotten place, with crosses atilt, the graves lost under weeds, and the little burying-house, which held a tiny altar and a series of old tiles depicting the Stations of the Cross, desecrated. The whole railed space, when tended carefully, seemed to speak of very benevolent despotism.

Halfway down the knoll on the side away from the Hall there used to be a row of cottages for estate-workers. The cottages looked on the stream, where the sheltered gardens with greenhouses and fruit trees were. Behind the gardens were the tennis courts, and upstream was a swimming pool.

Above: A map showing some of the features included in this chapter, including Castedge coal mine (click to enlarge).

Above: Jack Hewitt – far left with his daughter Phyllis – was manager of Castedge coal mine. (Click for more on the mine.)

The Hall even had its private coal-pit, going a mile and a half diagonally into the hill behind. I have mentioned it on page 53*. The Hall took all the lump coal – there was not much – and the rest, poorish stuff, was sold to farmers around at 5d. a hundredweight. If made up over a fire of good coal it lasted a tremendous time. A yarn is told of a farmer who went to America and when he returned found his fire still in!

A man who worked twelve years for the two last Gosling-Grimshawes told me: “There werna two finer ladies than them nowheer. It didna matter wheer they were, they’d move ta me. If they saw me i’ Buxton they’d pick me up they would an’ all! Aa were th’on’y man theer as werena a Catholic.

“Most chaps went ta th’private Catholic Chapel th’first Sunday they worked theer an’ then ad ta keep it up, but Aa didna. An’ they ne’er looked daan on me fer it. That’s what Aa liked abaat ’em.”

How far off those days seem! Sad memories, and the man who gave them has now been dead a dozen years. But well I recall his: “Yo’ should see th’rhodies theer, lad! Non a few flowers – miles on em. Flowers as far as from ‘ere ta them rocks yonder” (indicating quite a mile).

It was this recommendation that made me go to Errwood first, and I was in time, just before the benevolent reign ended.

My old friend did not stay quite to the end. A new bailiff had been engaged, he explained.

“Aa knew every yard o’ Errwood-reet up ta th’back door o’ th’ Cat an’ Fiddle. Aa were workin’ reet up theer, makin’ gaps up so as sheep couldna wander. Yo’ knows, if they got aat Macclesfield Forest way, we ne’er saw owt on em agen.

“They’re aw rogues that way! Any’ow ‘e come up ta me an’ said: ‘Well, John, Aa’m yo’re gaffer naa.’ So Aa looked at ‘im an’ Aa said: ‘Tha anna. Aa’ll walk far enough afore Aa’ll ‘ave thee fer mi gaffer.’

“So Aa gives mi fortnight’s notice. Aa were gassy then, an’ ad money in mi pocket, an’ in th’bank, an’ didna care fer noobody. Th’ old ladies wanted me ta stop, bur Aa wouldna. Aa’m an Englishman, an’ winna be ‘umble t’anybody.”

While the Hall was still occupied the grounds were opened at rhododendron time every spring for years so that anybody might enjoy the beauty.

But there was much smashing of bushes and taking of flowers, and eventually someone broke the nose off one of the religious figures that stood in niches in the wall round to the main steps. That was an insult the devout owners could not forgive and all privileges were withdrawn.

* (From page 53) Another old mine was behind Errwood Hall off the Goyt Valley. This within memory was worked by one man. The entrance was four feet high and three across, and the descent was by a gently sloping tunnel. There was a narrow pair of lines and the miner pushed a tub in front of him when he went down.

Near the entrance there is a large flat stone slab on which he tipped the coal when he returned. If he were going back underground he would chalk a name beside the coal so that the person could help himself.

John and Hannah Butler were my great-grandparents. Their daughter, Anna Genevieve Delores Pia Butler, was their daughter and my grandmother. She died in 1956 in Pretoria, South Africa. Two of her names were obviously taken from the Governess Miss Dolores de Ybarguen, a Spanish aristocrat who was taught at the estate school and was governess to the Grimshaw family and who died on a visit to Lourdes. My grandmother’s name of Genevieve was from Genevieve Grimshaw (who was my grandmother’s godmother). Genevieve married Robert Nixon and my maiden name was Nixon.

So, the ‘D de Y’ of the dedication plaque in St Joseph’s Shrine is Dolores de Ybarguen, the Spanish governess. Thanks, I wondered who D de Y was.