Above: The best place to see evidence of coal mining around Goyt’s Moss is from a lay-by beside the A54, heading west from Buxton, just before the junction to Congleton.

There’s a sign beside a stile warning walkers to take care, but the most dangerous shafts have been protected by wooden barriers.

An extensive 1997 archeological survey* of coal mining in Goyt’s Moss plotted some 200 pits and shafts. The earliest could date back to the late 17th century and were simple pits to extract coal lying just below the surface. But as these were exhausted, the miners were forced to dig deeper.

This fade compares today’s view of Derbyshire Bridge with a diagram showing just some of the many pits the archeologists identified in such a relatively small area. It also shows tracks used to transport coal from the shafts to local roads.

Coal was winched up the early shafts in buckets by hand. But it was a slow and laborious job, particularly as shafts became deeper, and horse-power soon replaced man-power.

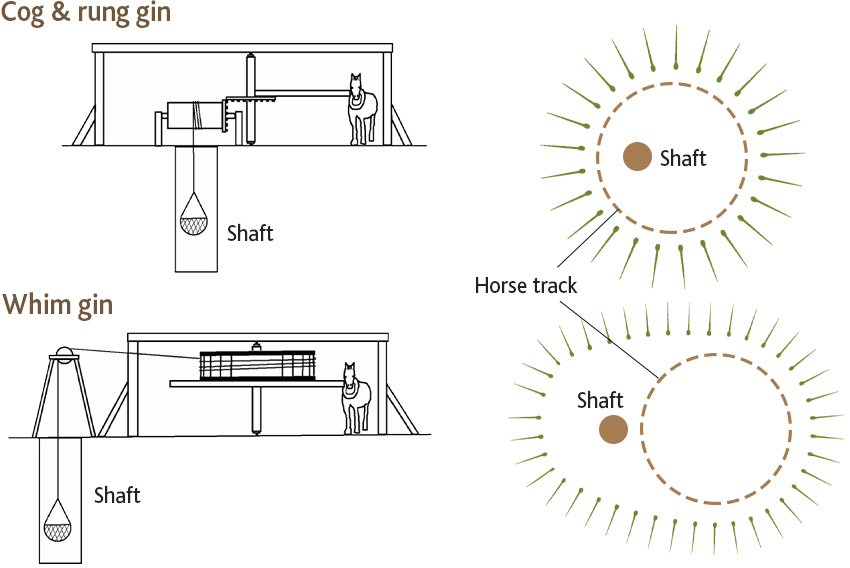

There were two types of horse-powered winches, known as gins, both of which had been used in England since the 15th century. Historians think the ‘cog and rung’ gin is the earlier as the ‘whim gin’ has a more efficient design.

Both types of gin leave fairly distinct footprints on the ground, and the Goyt’s Moss survey identified the remains of both across this barren landscape.

The miners would start by levelling the ground around the shaft to build the wooden structure. Whim gins were larger because the horse walked to one side of the shaft.

Over time, the weight of hooves compacted the ground, creating circles that left their mark. Either around the shaft, or to one side, depending on the type of gin.

Chatsworth records

The time of greatest coal production was between 1790 and 1816. Yet records kept at Chatsworth House show that in 1790, only 23 people were employed on a permanent basis at the Goyt’s Moss shafts, about half of them underground.

The coal was too poor quality to burn domestically, with most going to the Duke of Devonshire’s lime kilns on the slopes above Buxton (below where Solomon’s Temple now stands).

Goyt’s Moss Colliery was formally closed on 31st December 1893. The Mine abandonment certificate states the reason as “Area above water level worked out.”

Above: This pit shows the remains of stone ‘gining’ which was used to line the shafts. In most cases, the stones were collapsed into the shaft to seal it after all the accessible coal had been mined.

*To download a copy of the Goyt’s Moss archeological report, click here and enter ‘Goyt’s Moss Colliery’ in the title field. (Alan Roberts and John Leaches’ ‘The Coal Mines of Buxton’ is also packed full of information; see previous post for details.)

The Buxton Museum print is intriguing. The whim is obviously non-operational, or at least, is not connected to the shaft in the picture. The orientation of the pulleys would seem to indicate that it was never intended to be connected. The winding gear looks as if it is being driven from the wheel at the side of the building, but what is the motive force?

There is no evidence of a smoke stack, nor of water, and I don’t believe in gnomes or dwarfs. So what is going on? Is the shaft a trial shaft and are we looking at a manually operated percussive drill rig? Is it simply artistic license?

Yes very interesting, your observations Margaret, are very good indeed. Why is the headgear arrangement situated where it is, that is on a lower level than the whim? My guess is that it could possibly be used as a pumping shaft to drain workings on a lower level, possibly from a sump, which in mining terms relates to a small well or shaft where water was allowed to accumulate before it swamped the coal faces. A bucket, known as a Kibbel manual, would be lowered into the sump, then raised to the surface. This would be done on a regular basis, thereby keeping the lower beds as dry as possible.

With regards to the motive power, the whim gear predates steam, so therefore the driving force could only be either manually undertaken, or by a water-driven system using a clutching method. However, as you say Margaret, there is no evidence in the painting of any stream passing by. It could have been deliberately diverted through the shack where the clutching gear would have been assembled – a bit more comfortable in the winter months for the engineman.