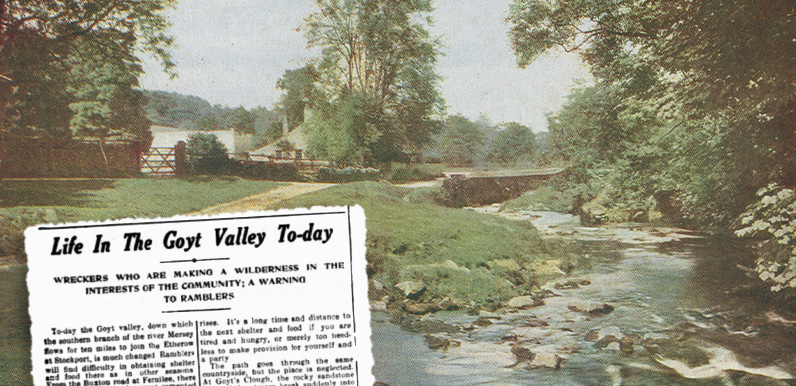

Above: A typically picturesque view along the River Goyt before the construction of the twin reservoirs – all now under water.

My thanks to Gail for sending this article which appeared in the Liverpool Echo of 6th February 1937, just a few months before the official opening of the first of the two Goyt Valley reservoirs, Fernilee.

Today the Goyt Valley, down which the southern branch of the river Mersey flows for ten miles to join the Etherow at Stockport, is much changed. Ramblers will find difficulty in obtaining shelter and food there, as in other seasons.

From the Buxton road at Fernilee, there is visible intrusion of a cemented dam. Beyond it the old hollow vale with its prattling streams a slack, deep reservoir of water for the people and industries of Stockport.

As the road rises higher, another form of damage is noticed; the farmsteads, houses and buildings between the road and the reservoir are pulled down or in the hands of “wreckers.”

I am told this is necessary to pureness of water in the Goyt reservoir, but drainage of the road, crushed rubber, spent engine oil, waste petrol and the relics of dripping loads and washing from tanks is not treated. A crusade against the in-wash of road poisons is overdue.

At the top of Long Hill, a track goes west to Goyt’s Bridge and the walker will find terrible changes there. Only the solitary arch of lichened stone remains at the meeting of the waters, a place originally of which Longfellow might have written:

Reflected in the tide the grey rocks stand and trembling shadows throw;

And the fair trees lean over side by side and see themselves below.

Above: The solitary arch of lichened stone; a rare photo of the packhorse bridge after all the surrounding buildings had been demolished.

Goyt’s Bridge is now a hungry place; the little community which occupied cottages and grey farmhouses is dispersed; the houses, sheds, huts, empty, derelict, most of them wrecked and carried away.

It is the same all the way up Goyt’s Clough to Axe Edge, and the marsh in which the Goyt or Mersey rises. It’s a long time and distance to the next shelter and food you are tired and hungry, or merely too heedless to make provisions for yourself and party.

The path goes through the same countryside, but the place is neglected. At Goyt’s Clough, the rock sandstone sides of the stream break suddenly into moorland escarpments and the stretch into the higher expanses that rise and fall until, far off, they meet the purple line of the horizon.

The ridges are outcrops sandstone beds, the steep-sided Goyt glen below is hollowed out in shale, and each band of grit and shale has its place in the series.

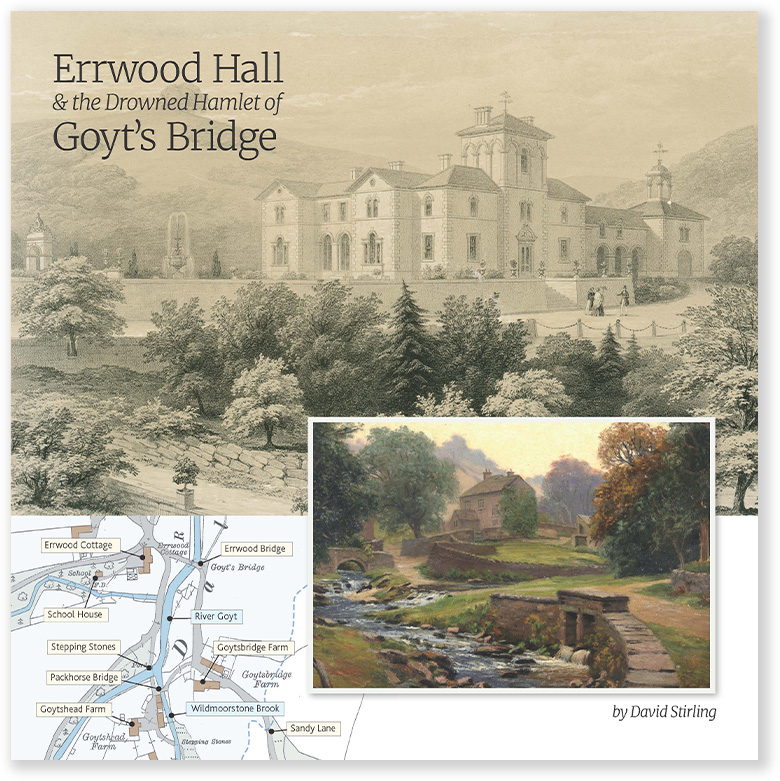

Errwood House, or a shelf above its twisted Clough and facing south, has been vacant for years. Built in white stone, in the Italian style, it was the seat of the Grimshawes, a family who remained staunchly Roman Catholic, for many generations.

I am told that the house now is awaiting some contractor who will remove it as builders’ material.

Above: Errwood Hall now lies in ruins. But it was once a magnificent country house, surrounded by rhododendrons bought here as ballast on the Grimshawe family’s ocean-going yacht.

What will happen to the grounds at Errwood, where in the “sixties” a mighty plantation of rhododendrons was made among other evergreens? Forty thousand trees were brought here.

Hollies you saw near the steep old drive, and pines and firs of majestic size. The rhododendrons flourished amazingly, and their display and dignity were well known to residents in Buxton and ramblers about the Goyt Valley.

In the flowering season they made a splendid sight. Tier above tier, a blaze of blooms seen from distant moorland roads and paths. There were ramparts of many tints, ranging from Tyrian purple to a faint flush of pink, with rose-red, scarlet, vermillion lake carnation, cardinal, gold, yellow and all relieved by the deep glossy gleam of the dense foliage.

I suppose neglect will destroy the beauty of Errwood in due time if the rhododendrons are not pulled up to be planted elsewhere. Stockport might want them to adorn some park or other.

In the meantime, every trace of human life and occupation is being removed from the Goyt Valley between the dam at Fernilee and the horizon at Axe Edge. Is it Good? Is it Good? I doubt it.

The Goyt will be quiet and hungry enough before the policy is finished. The few workers will be removed to distant homes, and human connection with the moorland glade will be lost. Emerson once wrote:

“Let us be silent that we might hear the whispers of the gods.”

…But no gods whisper in these wastes made by men.

I tell myself that I avoid the ruin of the hall during my wanderings in the valley because it will be “busy” there. In truth, I avoid it because I see its ruin as a vulgar act of vandalism.

What a pity such a magnificent building was demolished. I’d like to see the ruins. I think the short walk won’t be too long to leave my motorbike, as I do worry about it. Cars and bikes don’t mix, they don’t see us, I always try to park away from cars. Then there’s always thieves. I suppose a cesspit could have been put in these days and emptied. I suppose no-one was interested to take on the council to prevent it being demolished when the last of the family died. Rhododendrons can be a problem if they run wild.