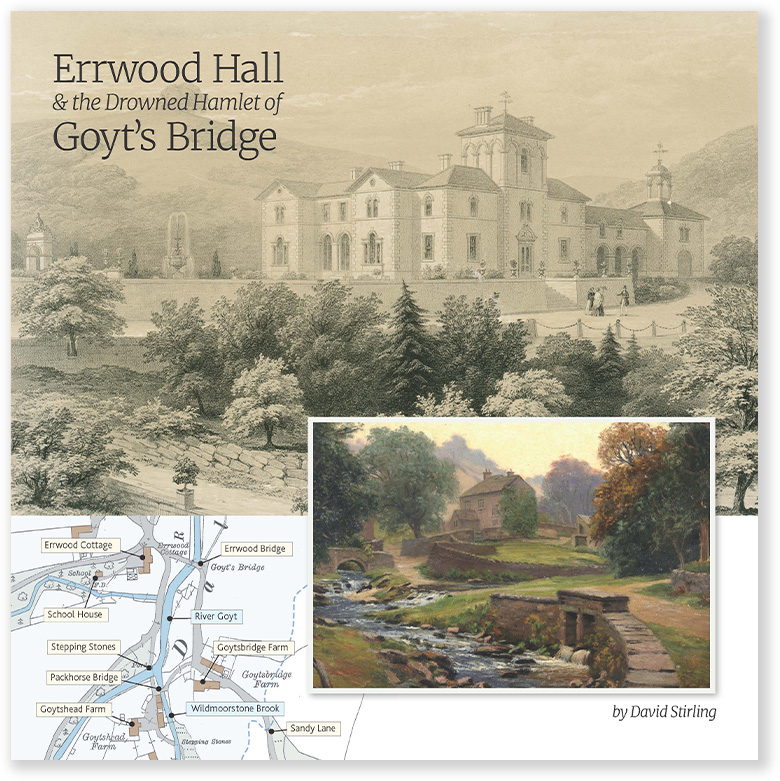

Above: A scene that would be common to anyone who travelled the roads in the 18th century: A hectic mix of coaches, carriages, horsemen, farmers with livestock, all having to pay their tolls before being allowed through the gates.

It’s no wonder the turnpike system caused a great deal of resentment. Particularly to locals with little money to spare.

Above: Alan’s book, Turnpike Roads Around Buxton, is available from High Peak Bookstore at Brierlow Bar.

My thanks to Alan Roberts for allowing me to reproduce this chapter from his ‘Turnpike Roads Around Buxton’ which explains what happened to the various turnpikes around Buxton.

On the 31st of October 1884, a ceremony took place on the Sheffield and Buxton Turnpike different in every way from the grand opening ceremony for the Wellington Road and Bridge, described in Chapter 1.

The Wellington Bridge ceremony had been a very formal, well organised occasion in the warmth of the day, pervaded by a confidence in the future of the Tumpike system; the ceremony at Hunter’s Bar tollgate in Sheffield on 31st October 1884 was a completely informal, spontaneous gathering in the cool of the night, waiting for the stroke of midnight. At that time, the Turnpike era came to an end in Sheffield and the Peak District.

During the day, John and Mary Spear, who had been the toll collectors at Hunter’s Bar tollgate for twelve months, had been clearing out their furniture ready for removal. The day had been enlivened by a dispute with & carter about a toll, which caused John Spear to lock the toll gate in the carter’s face until the toll had been paid.

During the day, two photographs had been taken of the toll house and toll gate, one of which included Mr Reuben Thompson’s Ecclesall Road horsebus, which was standing there at the time. That apart, the day had been fairly quiet.

Above: Old Hunter’s Bar in Sheffield. I think this must be the photograph Alan mentions (click to enlarge).

As midnight approached, a crowd of people began to assemble for what was seen as an historic occasion. The honour of being the last person to pass through the toll gate was given to Mr Haigh, a cab proprietor from Glossop Road.

On the stroke of midnight, to great cheers from the crowd, John Spear locked the door of the toll house and walked away. The crowd then rushed to the gate, lifted it off its hinges and threw it over a wall into a nearby field. The last of the Sheffield toll gates had gone.

What had started off as a benefit was now only a nuisance. What had been seen as a means of improving trade and communications was now only an anachronistic restriction.

Sheffield Town Council was already in negotiation with the Turnpike Trustees to buy Hunter’s Bar toll house, in order to demolish it for a road widening scheme that would give an improved tratfic flow between Brocco Bank and Sharrow Vale.

It was anticipated that the removal of the toll gate would lead to residential development of the Ecclesall area, which previously had been inhibited by the need to pay tolls to travel to the centre of Sheffield.

When the toll house was demolished, the stone gate posts were used for the entrance to Endcliffe Park. There they remained for many years but, when the present roundabout was built at Hunter’s Bar, it was decided to replace the gateposts in their original position and a small bar was constructed to make the whole look authentic.

The causes of the unpopularity of the Turnpike system are not hard to find.

From the beginning there had been resentment against the imposition of tolls, particularly where an existing road was upgraded and tolls imposed on a previously toll-free route. Over the years many toll houses were damaged and toll gates destroyed across the county.

Locally, toll gates and toll houses were destroyed at New Mills. According to an account in the Stockport Advertiser of 28th April 1838, these toll gates were originally erected on 14th July 1836 but were destroyed the same night. Later, they were rebuilt, only to be destroyed again, with the toll house, in December 1837. Four men were tried for these crimes but all were acquitted.

In Sheffield, an attempt was made to blow up Heeley toll house in 1883; some men climbed on to the roof of the toll house during the night and lowered a tin containing gunpowder through a hole that they had made. With a long fuse, they set off the gunpowder from the shelter of a nearby the resultant explosion blew a large hole in the roof of the toll house.

Above: The turnpikes became a focus of frustration and anger for locals, with protests often leading to violence and riots.

When the Turnpike system began to develop in the Peak District, much of the moorland and wilder country was unenclosed. Individuals were then free to find their own way from place to place by traditional routes across common land.

However, the Turnpike Trusts progressively acquired powers to fence or wall their roads and to restrict travellers to crossing them at only a limited number of places. In addition, the common land was progressively enclosed and the freedom to move across it at will was lost.

More and more, travellers were restricted to using the Turnpike roads, for the lack of any alternative.

Because of the massive inflation of recent years, it is easy to overlook how burdensome the tolls on the Turnpike Roads were to the bulk of the population. For instance, in 1790, coal miners in the Buxton area were earning 1/6 to 2/- per day for a six day week – about £24-32 per year, in 1985, the basic wage rate for a coal miner in Britain was £150 per week £7800 per year, or about 300 times as much.

By the values of the day, tolls were very high. For example, the simplest form of wheeled transport, a cart drawn by one horse, would have to pay a toll of 6d at most toll gates in 1830, equivalent to one quarter of a day’s wages.

The Turnpike Road System covered much of the country, so that the cost and inconvenience of tolls were well spread. However, one feature of Suxton’s situation, which would have aggravated the problem locally was the number of Turnpikes terminating at or near Buxton, of which there were six, compared to only one that passed through it.

Travelling along a singe Tumpike usually meant a limit to the number of tolls to be paid per day, but making a cross country journey involving several separate Tumpike Trusts meant paying fresh tolls on each road.

For instance, in 1830 a relatively simple cross country journey from Flash to Castleton (about 18 miles) would have involved paying the following tolls (for a cart drawn by one horse):

Flash Bar (Leek and Buxton TP): 5d

Ladmonlow (Leek and Buxton TP): 5d

Burbage (Macclesfield and Buxton TP): 3d

Stone Bench (Sheffield and Buxton TP): 6d

Barmoor Clough (Manchester and Buxton TP): 6d

Sparrowpit Gate (Sheffield and Buxton TP): 6d

Flatts Gate (Sheffield and Buxton TP): 6d

TOTAL: 3/1

The best part of two days’ wages would be needed even for such a short journey. Clearly, regular use of the Turnpike Roads was reserved for commercial users and for the well to do.

Locally, the high water mark of the Turnpike system was about 1825. After that time, there were virtually no improvements to the system and the Standard of maintenance dropped. Over ambitious improvement plans had left the Trusts with large debts, of which they were continually struggling to keep up with the interest without a corresponding increase in toll revenues.

The position was soon aggravated by the development of the railway system, as the funds available for capital investment rapidly diverted in that direction. Very soon, there were no new investment funds available to the Turnpike Trusts.

The largest of the local Trusts, the Manchester and Buxton Tumpike Trust, went into receivership in 1829 and a very tight financial regime was introduced.

Plans for improvements were lodged in respect of a branch from the Manchester and Buxton Turnpike to New Mills in 1829, branches from the Ashford and Buxton Turnpike at Monsal Dale to Barmooor Clough and Wardlow Mires in 1828, and a branch from the Congleton and Buxton Tumpike at Allgreave along the Dane Valley to Hug Bridge at Rushton Spencer in 1829.

None of these plans were implemented; the present road between the Manchester to Buxton road at Newtown and New Mills is part of a separate turnpike constructed along a different route, authorised in 1832.

Competition from the railways and other factors also led to a decline in toll income and, for the last sixty years of their existence, the main preoccupations of the Trusts were to maintain interest payments and to repay loans.

It was a time when the renewal Acts for the Trusts reduced interest payments, in some cases to zero, wrote off large amounts of unpaid interest and permitted Trusts to write off capital debts by payments at less than the face value of the debt.

By these means, the debts were eventually written off and, as they were, the Trusts were wound up.

Of those considered in this book, the years of closure were;

- Manchester and Buxton: 1872

- Leek and Buxton: 1875

- Macclesfield and Buxton: 1878

- Ashford and Buxton: 1878

- Congleton and Buxton: 1882

- Sheffield and Buxton: 1884

By Alan Roberts