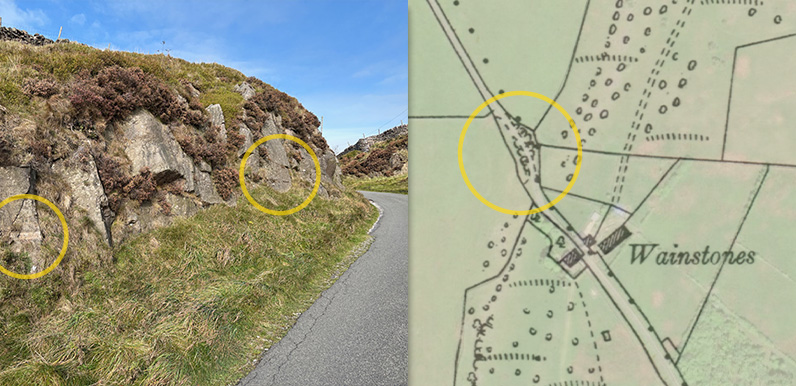

Above: The two religious phrases are crudely inscribed on the left of the cutting as the old Roman road heads north towards Whaley Bridge.

The map on the right dates to the early 1900s and shows how close the cutting lay to the Wainstones.

Christine recently posted a couple of photos on the Goyt Valley Facebook Group showing an intriguing pair of roughly carved religious phrases she’d discovered on rocks beside the old Roman road between Buxton and Whaley Bridge near a spot known as Wainstones*.

This ancient road once formed part of an extensive network of Roman highways linking cities in the northwest such as Chester with other large settlements in the Midlands such as Derby. The clear, clean spa-water springs of Buxton, then known as Aquae Arnemetiae (meaning ‘the waters of the godess Arnetia’), offered an ideal resting place for soldiers and merchants.

There were two roads running north from Buxton. One crossed a ford over the River Goyt, where the hamlet of Goyt’s Bridge lay before it vanished under the waters of Errwood Reservoir. And the other headed more directly north, through where Whaley Bridge sits today, and on towards the Roman fort of Ardotalia, near present-day Glossop.

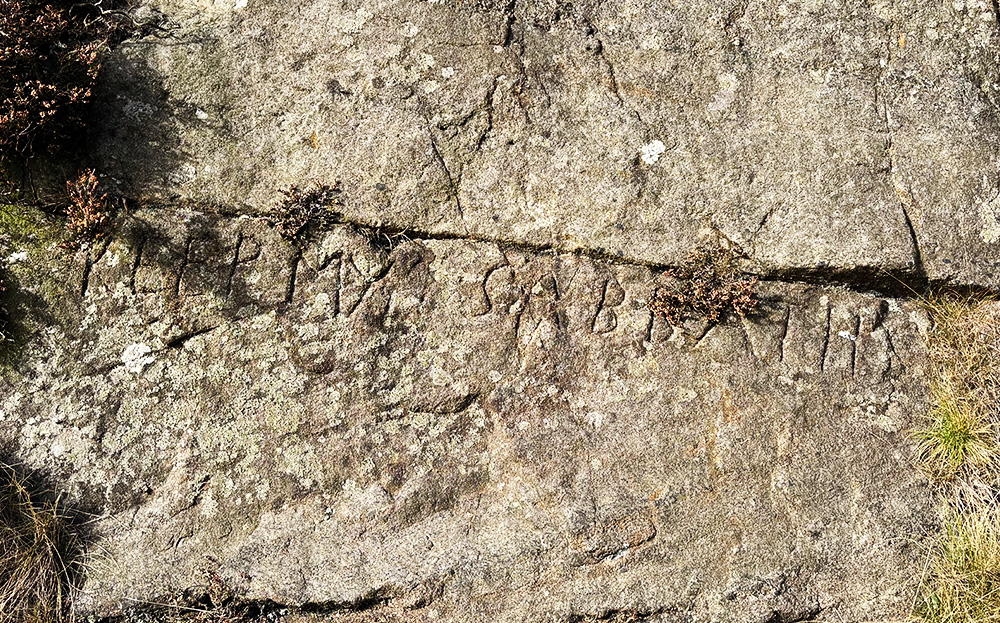

Above: The inscriptions are difficult to spot as they’re very weathered and usually in shadow. These photos were taken in mid morning and enhanced by increasing the contrast. (Click either to enlarge.)

The carvings are on the left of the road to Whaley Bridge, just beyond Whitehall Outward Centre (W3W location). The first reads ‘GOD IS FAITHFUL’. The second is just a short distance further and reads ‘KEEP MY SABBATH’. I’ve tried to discover more about them – particularly their likely age – but drawn a complete blank.

According to Alan Roberts in his book ‘Turnpike Roads Around Buxton’, the Wainstones rocks were exposed when the road was improved by blasting a cutting through the natural escarpment that ran across the route. (It’s still possible to see some of the drill holes used to pack the explosive powder – which may have come from the nearby Fernilee Gunpowder Mill.)

The inscriptions probably date to this improvement to the road, which would have been soon after 1725. Perhaps the workers objected to being forced to work on Sundays. Or just wanted to spread their religious message to those travelling the route.

I find the history of the turnpikes between Buxton and Whaley Bridge very confusing*. As I understand it, the first turnpike between Manchester and Buxton was authorised in 1725 after local magistrates complained that the existing road was…

…very ruinous , and many parts thereof almost impassable in the winter season, and in divers places so narrow, that it is becoming dangerous to persons passing through the same.

The old Roman road was the first to be improved under the turnpike laws. This was superseded some 50 years later by a completely new road, which may have been surveyed by the famous Blind Jack of Knaresborough. And then improved in the 1820s by cutting out some steep sections to create the present A5004 ‘Long Hill’ road.

*Page update

I asked Alan Roberts, author of ‘Turnpike Roads Around Buxton’, if he knew anything about the inscriptions, and also for any information on the sequence of the turnpikes between Buxton and Whaley Bridge. He responded:

The turnpike timetable was something like this:

1720s: first Manchester to Buxton route along the Roman road line, including the Wainstones cutting.

1770s: Major improvement – Long Hill, down into the valley and up again from Long Hill Farm area, following the existing straight length of road, a further straight section running behind the Shady Oak to Elnor Lane, along Elnor Lane to Whaley Bridge. Probably by Blind Jack but no firm evidence located. A very straight route, his style.

1820s: Existing route adopted to avoid large gradients on the 1770s version. Brief link with 1770s route at Fernilee

Stylistically, the 1770s/1820s routes are similar to the Buxton Macclesfield routes of the same periods, switching from fairly straight with steep sections to more wiggly routes to reduce gradients encountered by coaches and large wagons.

I have no information relating to crosses and carvings but the following snippet may be of interest:

At the time of the Jacobite Rebellion , the Scottish forces advancing towards London had reached Stockport by 1745. Big panic in London at Hanoverian Court – how can we stop them? A message to the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth – block the road to Derby from Stockport.

The Duke sends a message to an official at Chapel en le Frith – block the road. So the road was quickly blocked by a few local farm workers. The Scots, of course, continued their advance to Derby, further west.

The obvious site for a blockage is Wainstones, where a few large rocks on the floor of the cutting would block the road.

The lost Wainstones Cross

Another interesting feature of the old Roman road is that four ancient crosses once lay along the route. These may have been way-markers or boundary stones. One of the crosses was sited at Wainstones.

Above: The ancient Shallcross lost its cross in the dim and distant past. It probably dates back to the late 9th or 10th century and has been associated with the Viking invasion.

Only one of the four remains; the ‘Shallcross’, which was moved some years ago to a stone-walled enclosure beside the old Roman road as it reaches the outskirts of Whaley Bridge.

The nearby ‘Shallcross Incline’ formed part of the Cromford and High Peak Railway which once ran through the Goyt Valley, and provides another link to the area. (Walk 12 goes this way.)

*Wainstone is an ancient name derived from the Saxon word ‘wanian’, meaning to lament or grieve. So could well have marked the spot where an important chieftan was buried.

There is also a ‘missing’ cross at White Hall. In the book ‘Stone Crosses of the Peak’, mention is made of the Woman’s or Lady Cross which local legend said lay at the junction of the path from Combs and the Roman road. No trace exists today. However, during my 45 year stay at White Hall I managed to locate the site of the cross. If you would like more information please email me.

One theory is that the penitential crosses were toppled/removed, probably in Cromwell’s time and the site was (in a way) rededicated by the road workers by the addition of the carvings. Regarding the possibility of the Duke of Devonshire ordering the blocking of the road to impede the approaching Scots, this is new to me, but entirely plausible.